The Enviro-Legal Sniff Test of Dog Meat Consumption in Nagaland

Rudraksh Pathak* & Arya Mishra**

Abstract

The legal and ethical discourse surrounding dog meat consumption in Nagaland brings to light the delicate balance between cultural identity, indigenous rights, and evolving animal welfare standards. Rooted in the culinary traditions of the Naga people, the practice has long been a marker of cultural heritage, yet it faces increasing scrutiny under constitutional and international legal frameworks that emphasize animal rights and public health. The Guwahati High Court’s decision in Neizevolie Kuotsu v. State of Nagaland set aside the ban on commercial sale and import of dog meat, recognizing the importance of traditional livelihoods and autonomy. However, concerns persist regarding the welfare of animals in the trade, as documented by Humane Society International, which has reported instances of inhumane transport and slaughter. Additionally, the potential public health risks linked to zoonotic diseases, including rabies and foodborne illnesses, highlight the need for regulatory oversight. This paper juxtaposes the Nagaland case with South Korea’s 2024 legislative ban on dog meat, where evolving societal attitudes and declining demand led to legal intervention. While acknowledging the significance of cultural relativism and indigenous rights, this study advocates for a balanced approach—one that respects Naga traditions while fostering dialogue on ethical consumption, humane treatment of animals, and public health safeguards. By situating the issue within constitutional morality, the prevention principle, and global legal perspectives, it underscores the need for nuanced policy responses that harmonize cultural heritage with responsible legal and ethical frameworks

Key Words: Cultural Heritage, Animal Welfare, Dog Meat Regulation, Prevention Principle, Public Health

- Introduction

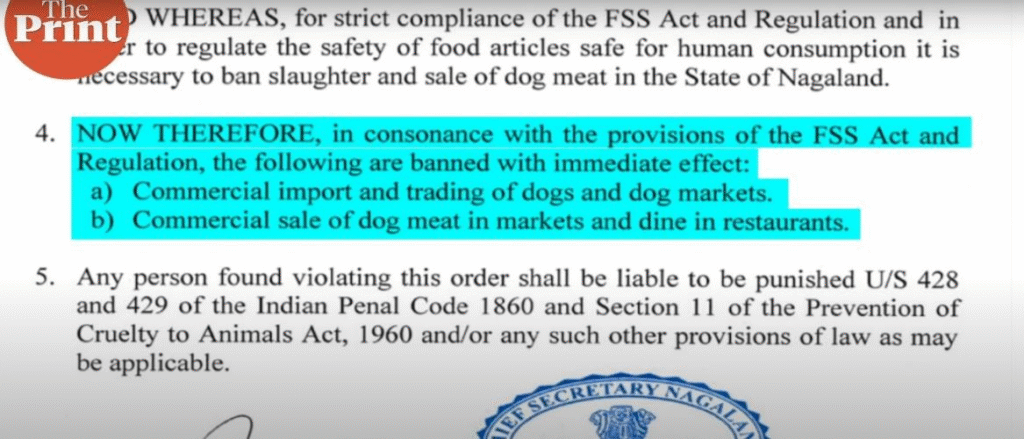

People of the Hills, the Nagas, are people who have a distinct food habit, with rice and meat being their staple diet. And the step-motherly treatment towards the Nagas due to their culinary habits, specifically the least-sensationalised dog meat consumption, has made them very protective towards their local cuisine. The issue of dog meat consumption has exacerbated the differences between the locals there and in the other parts of India, as some find this ‘barbaric’. But this strife strikes at the core of ‘animal welfare’ and ‘right to safe and healthy environment’. The discussion over dog meat became relevant a few years back, when simply a notification was issued in pursuance of the FSS Regulation, 2011 which banned the commercial import and commercial sale of dog meat in the state of Nagaland. In Guwahati High Court the validity of this ban was challenged in the case of Neizevolie Kuotsu v. State of Nagaland, citing livelihood of the petitioners as one of the major reasons, wherein the court set aside the Notification thus issued.

The research would focus on how the narrative of trade and consumption of dog meat has put ‘Cultural Identity of Nagas’ and ‘Animal Rights’ at loggerheads, further challenging the ‘right to safe and healthy environment’ (understood in the light of Customary International Law and Constitutional Morality). To draw a comparative analysis, we will delve into the object and rationale of the recent South Korean Ban as a model of law to systematically challenge the trade and consumption of the dog meat from the perspective of international standards. In furtherance of same, how this trade and consumption is in contravention to the ‘preventive principle’ is a thought that requires further deliberation.

- Cultural Identity Versus Animal Rights

- Cultural Relativism of the Nagas

The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) published a circular on August 6, 2014, defining animals, carcasses, and meat under Regulation 2.5 of the Food Safety and Standards Regulation, 2011, with sub-regulation 2.5.1(a) providing the definition of “animal”. The FSS Act, 2006 and Regulation, 2011prohibit the killing of animals of any other species save the one specified in regulation 2.5.1(a). The contested order of prohibition was issued in accordance with this directive. According to FSS Regulation 2.5.1(a), an “animal” is defined as any of the following: poultry, fish, ovines, caprines, bovines, and suillines.

The Court noted that dogs and canines are not included in the definition of “animals” under Regulation 2.5.1(a) of the FSS Regulation, 2011 because dog meat is only consumed in a few areas of the North-eastern states and the concept of eating dog meat is foreign to other regions of the country. The petitioners are able to support themselves by transporting dogs and selling dog meat, therefore the court also noted that dog meat appears to be a standard practice and food among the Nagas even in the current times. Further court also observed some procedural irregularity in terms of issuing this notification on the part of state and set aside the decision considering it as a roadblock for the livelihood of the petitioners.

Figure 1 (Source: The Print)

The legal interpretation of the court was well suited if understood in context to the cultural understanding of this practice. But, the court failed to notice some other universal animal welfare related principles that assure wide-ranging rights to these companion animals. When the court took notice of this ban and reflected upon this consumption being alien to other regions of the nation, it specifically impressed upon its culturally relative culinary habit of dog meat consumption. This ban though driven with a noble cause, directly hits at the cultural identity of the Nagas. Therefore, before imposing the ban, culturally relativistic standards of the community should have been taken into consideration.

But the unfounded, constant imposition of terms such as ‘savage’, ‘barbaric’ and ‘inhuman’ on the Nagaland dog meat eaters (with Sema Lotha and Ao being some of the dog-meat eating communities) has further sparked this controversy.

- International Law on Preservation of Cultural Identity of Such Tribes from the Lens of Cultural Relativism

Law and culture intersect in various international spheres, including human rights, cultural autonomy, heritage protection, dispute resolution, use of force, and international environmental and development law. To play a more confident and effective role in global affairs, the impact of culture on the aforementioned legal areas has to be considered from the lens of international law.

Modern anthropologists are key proponents of cultural relativism. Two key concepts are proposed as the foundation for cultural relativism. The variety of civilizations is undeniable and may be chronicled indefinitely. The concept of diversity leads to the conclusion that evaluating and judging behavior is influenced by one’s cultural background. In the words of a researcher, “it is a corollary that standards, no matter in what aspect of behavior, range in different cultures from the positive to the negative pole.” A group’s norms and values are determined by its cultural context. Some argue that cultural practices and institutions emerge at random, regardless of their efficiency or practicality. This displays a really illogical view of civilization.

Adda Bozeman’s elucidation on the connection between cultural relativism and international law is often seen as contentious. She goes on to say that “profound differences between Western legal theories and structures and those of Africa, China and India must preclude attainment of a universalistic legal system of predominantly Western orientation.” Non-Western cultures sometimes exhibit tendencies that contradict Western values, such as “suspicion of the West is rife, conflict is the norm, and peace is an alien concept.”

This brings us to delve into the outlook of International Law in terms of balancing the universal rights as well as protecting the tribal rights within the culturally relativistic bounds of a community. Particular provisions exist in different national legislations such as Biological Diversity Act, 2002, Forest Rights Act, 2006, to ensure aboriginal subsistence rights, in addition to the general requirements in international law, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which imposes a responsibility on nations to affirmatively defend minority rights. Since these rights are the primary means by which indigenous people may attain food security, the slaughter of animals in the course of defending those rights is a legitimate use of a resource that would otherwise be illegal.

Different cultural ideas about the appropriateness of animal slaughter are reflected in the ways that animal harm constitutes a kind of self-expression in some cultures that contrasts with conventional beliefs about animal maltreatment as essentially illegal or malicious. And therefore, the branding of Nagas as ‘barbaric’ based upon their cultural practice is a bit harsh. For instance, International Whaling Commission suggests that whaling must be done as humanely as possible; further accepting that this type of animal suffering is acceptable for cultural reasons. According to the Makah people of North America, conducting whale hunts “requires rituals and ceremonies which are deeply spiritual”, and whaling is fundamental to their culture and social structure. Similarly, Nagas also associate some ritual and beliefs with the consumption of dog meat. The scientific validity of the claims has remained unquestioned so far.

Figure 2 (Source: The Print)

- Recognition of Animal Rights in International Jurisprudence

The anthropocentric formulation of a human right to a healthy environment may appear to be an unhelpful framework for animal rights, yet it is really quite informative. Rights of Nature have two origins. First, “these rights arose from the recent acknowledgment that present environmental legislation, including the human right to a healthy environment, has failed to address the global ecological issue, particularly climate change. Second, indigenous traditions and law that have always treated humans as part of nature, rather than distinct from it, have long offered a framework and strategy based on natural rights principles.” In the domain of animals, a similar statement would be a human right to animal protection, which states that people have the right to have all animals sufficiently protected. This may appear to be strange terminology, yet it is consistent with how legal systems now regard animals.

Nature’s rights are not widely recognised, yet they have the potential for expansion and effect. Ecuador was the first country to recognise natural rights in its constitution. The first paragraph of Article 71 states: “Nature, or Pacha Mama, where life is reproduced and occurs, has the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes.” Similarly, Bolivia also used this strategy in the Law on the Rights of Mother Earth (2010).

At the most fundamental level, if we have proven that nature contains rights, and if nature includes animals, then rights-based claims might be filed on the behalf of animals as well. This potential is shown by the Wild Parrot case, which was decided in 2008 by Brazil’s Superior Court of Justice. The case included a person who had confined a single wild animal, a blue-fronted parrot, in captivity for almost two decades and in not so adequate living conditions. Further, Brazilian court invoked Article 225 of their Constitution and stated that “Article 225 is an anthropocentric human right to an ecologically balanced environment, not rights of nature provision, and the constitutional framing of animal protection comes through an environmental, fauna and flora framework.” The court advocated for a reconsideration of the “Kantian, anthropocentric, and individualistic concept of human dignity.” Dignity should be reformed to recognize “an intrinsic value conferred to non-human sensitive beings, whose moral status would be recognized and would share with human beings the same moral community.”

In the animal setting, the notion that humans are capable of making such a judgment has been challenged. In Naruto v. Slater, the Ninth Circuit expressed its concerns vis-a-vis the organisation that brought the lawsuit on behalf of Naruto, a crested macaque. Judge Smith agreed in part, saying, “but what about the interests of animals? We are genuinely asking what another species desires. We have millennia of expertise knowing humankind’s interests and aspirations. That is not always true for animals.”

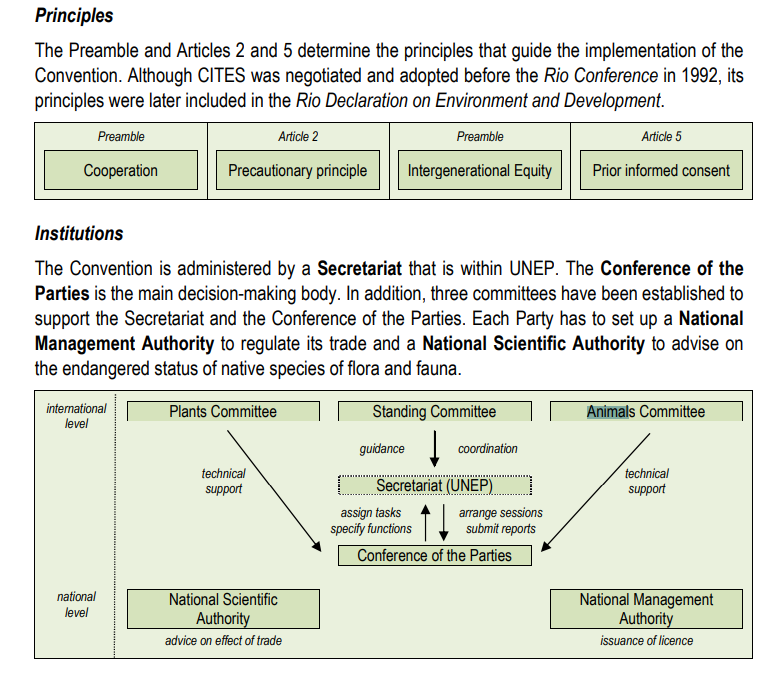

Figure 3 (Source: MEA-HANDBOOK-VIETNAM)

This figure shows the initiatives under CITES by UNEP and subsequent formation of a compliance mechanism. Further, emphasizing upon the collective will of the global community in terms of their desire to protect animal rights.

Therefore, in we compare the above jurisprudence with situation at hand i.e. importing, transporting, cramming and selling the dog meat in Nagaland; the situation in which these dogs are crammed is highly unsanitary conditions, without adequate food, water and other basic resources (as will be observed in the reports by Humane Society International and some other flag bearers in this regard. They are beaten, tortured, confined and subjected to other forms of cruelties, which are much graver as compared to the one in Wild-Parrots Case.

- Subjugation of Animal Rights in Nagaland and its Spill-Over Effect on Public Health

“Our own investigation in Nagaland showed terrified dogs being subjected to horrific deaths in some of the worst inhumanity to animals HSI/India has ever witnessed. And the dogs we have rescued from this trade over the years have had to learn to trust humans again after the cruel treatment they endured.” These were the words of Alokparna Sengupta, Humane Society International’s (India office) Managing Director. According to HIS, which is a renowned animal rescue NGO working in this direction, around 30,000 dogs are smuggled into Nagaland and sold in the live markets and many of them are beaten to death with wooden clubs due to poor implementation of FSS Regulation 2011.

In fact, former Minister of Animal Husbandry Smt. Maneka Gandhi urged people to step up against the dog meat consumption in pursuance of which around 1,25,000 people wrote to Nagaland government to stop this practice.

Figure 4 (Source: Humane Society International)

This practice is also in contravention with the constitutional morality as enshrined in Article 51A (g) and Article 48A of the Directive Principles of State Policy, of Constitution of India. They place a duty on the State and its people to show compassion for every living being. In Animal Welfare Board of India v. A. Nagaraja, the Supreme Court interpreted these clauses and concluded that “every animal has an inherent right to live, with the exception of human necessity.”

Can it be a human necessity if a greater part of young Naga generation abstains from eating dog meat? This logical argument is pretty similar to that of the rationale before the South Korean ban on dog meat consumption earlier this 2024, which would be dealt in detail further.

Moreover, if we specifically refer to Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960 under Sections 11(1)(i) and 11(1)(j) of the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (PCA) Act, 1960, stray dogs are protected from being relocated. Stray dogs are also protected by the rules passed under Section 38 of the PCA Act, the Animal Birth Control (Dogs) Rules, 2001. It is also against the Stray Dog Management Rules (2001) to kill stray dogs. The Sections 428 and 429 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 also forbid killing, maiming, or poisoning animals valued at more than 10 rupees. Dogs that are traded for meat are typically worth thousands of rupees; therefore, they are protected by the law.

The sheer ignorance towards the rights of this breed and incessant consumption is not only in contravention with the letter and spirit of law but is also heavily costing many people in terms of their mental and physical health. Therefore, taking into account global health disasters such as Covid-19, the regulation of live market is very necessary.

A unique observation was made by University of Calabar Teaching Hospital (UCTH), Calabar in 2013 where many of the patients were clinically diagnosed with rabies and admitted to UCTH (which serves as a referral facility for whole southern Nigerian state of Cross River). “Ten peculiar cases of rabies in subjects aged 3 to 52 years were recorded in 2013 in UCTH. Eight of the cases were male and apparently got infected directly or indirectly through the trade in stray dogs for human consumption. None had proper PEP and all patients died. Stray dog trade, fuelled by eating of dog meat, is a risk factor for human and animal rabies in Calabar, southern Nigeria.”

Additionally, Professor Senatori made some crucial contributions in regards to the companion animal law after working for decades in this field, in which she made a very bold observation; Research shows that people who hurt companion animals don’t usually stop there. According to the Link theory, “cruelty to animals is linked to family violence and, more broadly, violence toward humans generally.” Hence, the spill-over effect of this cruelty in general towards these companion animals can be long-term.

All these pieces of research act as evidence of the ‘violation of these animal rights catapulting the spill-over effect’, further endangering the ‘right to live in healthy and safe environment’. In R.L. & E. Kendra, Dehradun v. State of UP, this right was recognized as a part of Article 21 of the Constitution of India. Even art 19(1)(g) guarantees Freedom of Trade and Occupation subject to public safety and peace.

Even if we analyze it from the perspective of underlying international standards, The WHO defines environment and health as “the direct pathological effects of chemicals, radiation, and biological agents, as well as the impact of the physical, psychological, social, and aesthetic environment, such as housing, urban development, land use, and transportation.” Access to adequate drinking water, sanitation, and food hygiene can reduce diarrheal illnesses i.e. they are preventable, which kill 1.5 million people annually. Point being that WHO has intentionally given a very wide ambit to encompass various factors that sustain a symbiotic relationship between the domains of ‘environment’ and ‘health’. Further there has been a constant emphasis on ‘prevention’. Prevention is not just a word; it is a principle that enjoys a significant position in the field of International Environmental Law.

Understanding the notion of prevention requires understanding the genesis of the no harm rule, which was developed in the Trail Smelter case. Several scholars believe this award to be the first expression of the notion of prevention. The Dominion of Canada was held liable for pollution discharged into the atmosphere by a foundry. The court ruled that the government should have ensured that the plant was operating in accordance with international law, which requires all states to protect other states from harm caused by individuals within their jurisdiction.

This principle of ‘prevention’ allows for early intervention to safeguard the environment. It is no longer enough to repair losses once they have happened; it is also necessary to prevent those damages from arising in the first place. This principle isn’t as broad as the precautionary principle. In a nutshell, it suggests that preventing is preferable to repairing.

According to the International Law Commission’s (ILC) Draft Articles on Prevention of Transboundary Harm from Hazardous Activities (2001: General commentary, para 3, “prevention is a customary international law principle that states have the right to carry out activities within their territory or jurisdiction.” The Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros case highlights the importance of prevention in environmental protection due to the irreversible nature of environmental damage and the limitations of repair mechanisms.

Therefore, after taking into account the scientific reports which explicitly establish that consumption of dog meat might have physical as well as psychological implications the consumption of such meat needs to be regulated.

- Change In Contemporary Realities: The South Korean Case Study

When the locals were interviewed thy had this perception that “eating dog meat was once seen as a way to improve stamina in the humid Korean summer. But the practise has become rare – largely limited to some older people and specific restaurants. Now more Koreans consider dogs as family pets and as criticism of how the dogs are slaughtered has grown.” The practices were also becoming inhuman with dogs being crammed, electrocuted and hanged. This bill to ban dog meat consumption was passed by a vote of 208 to 0 in the National Assembly. There will be a three-year grace period before it takes effect.

With a growing understanding of dogs as pet/companion animals the younger generation specifically rejected this old practice. In a study by Gallup Korea, 64% of participants opposed consuming dog meat, a significant rise from a comparable survey conducted in 2015. Just 8% of respondents in 2022 reported having eaten dog meat in the previous year, down from 27% in 2015.Further, the government figures suggest that, the number of restaurants in Seoul’s capital that served dogs decreased by 40% between 2005 and 2014 as a result of the decrease in customer demand.Further, more than 94% of respondents to a poll conducted by the Seoul-based think tank Animal Welfare Awareness, Research and Education stated they had not eaten dog meat in the previous year, and almost 93% said they would not do so going forward.

Therefore, the changing realities and the awareness in regards to the companion animals and their rights have shaped this discourse to a great extent.

- Conclusion

The setting aside of the ban by the Guwahati court well encompassed the understanding of ‘cultural relativism’ of the Nagas. But this ratio was not adequately balanced with animal welfare and necessary rights that have been vested in them by the constitution of India. International Law in its pursuit of preserving the rights of such minorities goes to the extent of recognizing the animal harm in certain exceptional cases where cultural identity and cultural reasons are in picture. This approach of International Law and its principles is debateable. Further, this import, transportation, cramming and consumption is in contravention to our constitution as well as the relevant sections of Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act as well as the long-standing jurisprudence of international environmental law. The studies also show how ‘this violation of animal rights’ is having a spill-over effect on the ‘right to safe and healthy environment’ of the stakeholders at large and is in violation of the ‘prevention principle’. The South Korean ban is one such recent instance which pondered upon this spill-over effect and offered a domain which craves scientific literature suited as per the contemporary realities.

✦✦✦